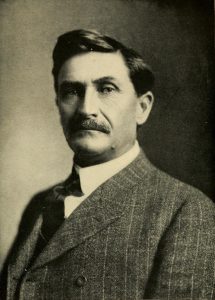

The great western historian, C.L. Sonnichsen, called Eugene Manlove Rhodes “The Bard of Tularosa”. The accolade was not casually considered. Rhodes’s, a true southwest cowboy, wrote stories and poems that painted the “hired man with a horse” as a western warrior of muscle and courage, a veritable knight of the desert, his women always virtuous and admirable. However, in 1933, a year before he died, Rhodes asked that his books never be advertised as “Westerns”; rather, he wanted his books fit to be read by “the Discriminating Reader,” and his work called “New Mexico stories.” His point being that The Virginian and The Log of a Cowboy were not “Westerns” (“…where “Western” has come to mean – worthless, trashy, blood and thunder stuff…”) and neither was his work.

The life and work of arguably the best writer of “New Mexico stories” in the early twentieth century have faded from view. His stories are no longer in print. Few of the reading public and relatively few writers, including western writers, are aware of Eugene Manlove Rhodes or his work. He published his first seven novels and numerous magazine stories between 1910 and 1926 while living in Apalachin New York during his “self-imposed exile” from New Mexico. His novels include the classics Pasó Por Aqui, Good Men and True, Bransford of Rainbow Range (The Little Eohippus), and The Trusty Knaves. These tales are unexcelled in painting vivid pictures of southern New Mexico landscapes, in accurately capturing the language and personalities of its men and women, and in describing the hard work and skills it took to survive and perhaps even succeed on the rough desert range and its mountains, places he called “the land of enchantment.”

Eugene Manlove Rhodes’s life and work might be better known today if his publisher had used, in a planned major advertising campaign, the exciting, true story of how Rhodes helped Oliver Lee and Jim Gililland outfox Pat Garrett to avoid a deadly confrontation. It is a story that, even today, might still bring one of the west’s greatest storytellers long overdue, renewed interest and recognition he richly deserves and bring wider recognition to Pat Garrett’s last major case. It is the story told here.

On February 1, 1896, Albert Fountain and his eight year-old son, Henry, vanished near White Sands, New Mexico Territory. Fountain was a tough frontiersman who had led posses and militias to wipeout bandit gangs and marauding Apaches, an attorney, a newspaper publisher, and a leading Republican. He was returning home from a meeting of the grand jury in Lincoln, New Mexico. He had obtained indictments against a number of small ranchers and itinerant cowboys for cattle rustling. Among them was an indictment for Oliver Lee, one of Fountain’s primary Democratic opponents, and a leading light among the small ranchers struggling to survive after a seven-year drought. Within two days after the Fountains disappeared, while posses were still combing the desert looking for some sign of them, Lee was blamed for their murder and Republican oriented newspapers in Las Cruces and El Paso called for him to be lynched.

Under tremendous pressure for swift justice, Territorial Governor William T. Thornton brought Pat Garrett out of retirement in Uvalde, Texas to find and capture the killers. Thornton also hired the Pinkerton Detective Agency to help Garrett gather evidence. He told Garrett and the Pinkerton detectives that he believed Oliver Lee and his friends were behind the murders. Rewards totaling $16,000 were offered for the apprehension and conviction of the murderers.

Garrett began gathering evidence, his attention focused on Lee and his friends and the big monetary rewards for solving the case. On April 2, 1898, Garrett obtained a bench warrant from Judge Franklin Parker in Las Cruces, New Mexico Territory, for the arrest of Oliver Lee and three of his friends, Bill McNew, Jim Gililland, and Bill Carr. He arrested McNew and Carr in Las Cruces, the day after he obtained the warrant. No attempt was made to arrest Lee and Gililland who had already left town. Within two weeks Carr was released for lack of evidence. McNew was illegally kept in the Las Cruces jail (in solitary confinement) for nearly a year while Garrett tried to make him admit that Lee was behind the murders. Lee’s ranches lay in the Tularosa basin less than sixty miles from Las Cruces. However, in range wars and against horse and cattle thieves, Lee and his friends had proven themselves deadly with rifles and revolvers. For the next three months, Garrett bided his time waiting to catch Lee and Gililland in an indefensible position.

Following a tip, Garrett and a posse appeared at a Lee ranch, Wildy Well, in the early morning hours of July 10, 1898. Lee and Jim Gililland were asleep on the roof of the adobe ranch house. Garrett and an inexperienced deputy, Kent Kearney, climbed up to the edge of the roof’s parapet and opened fire without warning. With bullets ripping into the roof just under their bedrolls, Lee and Gililland returned fire. The Garrett posse, getting the worst of the fight, was trapped under a lean-to next to the house. Lee goaded Garrett to tell the truth about the fight, and to admit that Lee and Gililland had put his five-man posse in a tight spot. Letting the posse retreat, Lee and Gililland disappeared into the surrounding mountains. Kearney, mortally wounded, died two days later. Lee believed that if he surrendered to Garrett, he would be “shot while trying to escape,” and vowed that would never happen.

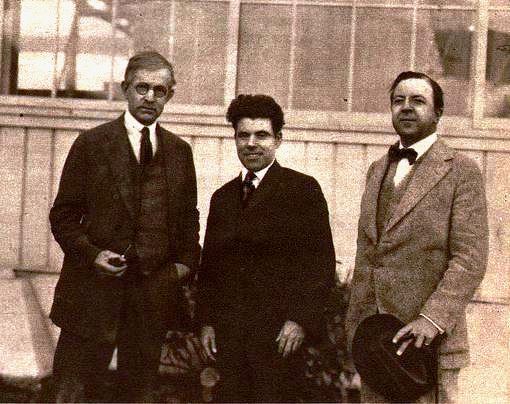

Lee’s attorney was Albert Fall, future Secretary of the Interior under Warren Harding, and the only one to serve prison time for the Teapot Dome Scandal. During the months Lee and Gililland were on the run, Fall managed to align the political stars in the territorial legislature with Governor Miguel Otero. They agreed to divide huge Doña County, where the Fountain murders occurred, into two counties, the new one being named Otero County. The spot where the Fountains were murdered lay just inside the new county where Pat Garrett had no legal authority. The Governor named future governor and friend of Oliver Lee, George Curry, the new county sheriff. After Curry agreed not to turn them over to Garrett, Lee and Gililland surrendered to Judge Parker, March 13, 1899. Their trial for the murder of Henry Fountain, held in the little mining town of Hillsboro, fifty miles north of Las Cruces, began May 25, 1899. Lasting eighteen days with night sessions and with seventy-five subpoenaed witnesses, the “Trial of the Century” ended with the jury deliberating eight minutes and declaring Lee and Gililland not guilty.

Gene Rhodes owned a small ranch in a remote canyon pass that crossed over the San Andres Mountains. The canyon provided an east to west passage across the mountains for hard-eyed men chased by riders with badges and warrants. Rhodes was host to the likes of Black Jack Ketchum, Bill Doolin, and Al Jennings. He narrowly escaped being murdered by Apache Kid who rested his horses in Rhodes’s pasture. Hiding from Garrett and his posses, Lee and Gililland spent time at Rhodes’s ranch. Never staying in one place for very long, Lee and Gililland, wandered the Sacramento, San Andres, and Black Range Mountains. Rhodes often went with them.

A bloodhound with his nose on their trail, Garrett combed the mountains for Lee and Gililland without success. However, there are stories of narrow misses. C.L. Sonnichsen relates that Lee once met Garrett face to face on a public road, but his long beard and tattered clothes gave him an appearance so different from his old dapper self that Garrett went by without a second look.

On March 13, 1899, Lee and Gililland, with Rhodes accompanying them, headed for Las Cruces to surrender. They boarded the south-bound Santa Fe train at Aleman station, a few miles south of Engle, New Mexico Territory. Continuing to wear their long beards and shabby clothes, Lee, at Rhodes’s suggestion, had replaced his fine white Stetson with a faded blue section hand’s cap pulled down low over his eyes and Gililland wore blue glasses. They took seats in the day car. The train rolled out of Aleman, rapidly gaining speed. Pat Garrett, the last man in New Mexico Territory Lee and Gililland wanted to see, drifted into their field of view and walked past them as he headed for the smoking car. Rhodes, seeing Lee’s hand slowly reach for his revolver and then relax, cringed when he saw Garrett stopped momentarily in the aisle to acknowledge Texas Ranger, Captain John Hughes who was bringing a prisoner from Santa Fe back to Texas. Hughes and his prisoner were sitting just a few seats ahead of them. Garrett and Hughes spoke briefly before Garrett went on to the smoking car.

At every stop, Garrett left the smoking car and walked through the train eyeing the passengers. At one stop, Hughes chained his prisoner to his seat and walked the train single file with Garrett. They stopped to look out the window by the seats where Lee, Gililland, and Rhodes sat, nonchalant but tensed for action. Saying nothing, Garrett and Hughes turned and continued their walk through the train. With the two famous lawmen on board, Rhodes decided it was time to contact Judge Parker in Las Cruces. When the train stopped in Rincon, he got off and sent Parker a telegram stating that Oliver Lee and Jim Gililland were on their way to surrender. At Rincon, another friend, Tom Hall, joined them. In Las Cruces Judge Parker deputized Rhodes and Hall to guard Lee and Gililland and to take possession of their guns while he determined what to do with his prisoners. After some study, he ordered them jailed in Socorro until a jail was built in Alamogordo, the Otero County Seat.

At the trial in Hillsboro, emotions ran high on both sides. Lee and Gililland claimed they had reason to believe there were plans afoot for their assassination and requested Judge Parker provide them with special guards. Judge Parker made Gene Rhodes one of those guards.

After the verdict in Hillsboro, Lee and Gililland were returned to the jail in Alamogordo to await trial for the murder of Kent Kearney. After their unequivocal loss in Hillsboro, the territorial attorneys decided not to prosecute for the Kearney shooting. Lee and Gililland were released in Alamogordo September 1899.

After the trial in Hillsboro, Gene Rhodes had other things on his mind. On August 9, 1899, he married a widow, May Davison Purple, in Apalachin, New York. She was an admirer of his poetry and had corresponded with him for over two years. Events and income forced Gene, May, and her two small sons, to leave New Mexico and settle near May’s parents in Apalachin. For nearly twenty-five years Gene farmed and wrote and May typed his manuscripts. It was the most productive time of his writing life.

Rhodes’s work, often published in the Saturday Evening Post, was much appreciated by western readers, but generally ignored by eastern critics. His publisher, ready to bring out Bransford in Arcadia (the book title of “The Little Eohippus”), wanted to use the exciting story of Rhodes’ involvement with Oliver Lee to generate widespread interest in his work. Albert Fall was contacted to ask his approval. W. H. Hutchinson quotes Fall’s reply to Roland Holt, Vice-President, Henry Holt Company, in a letter dated 16 March 1914. Fall’s answer is telling both for the character of the Southwest in 1914 and for the probable controversy that would have generated the widespread recognition Rhodes’ work deserved. Fall wrote:

“My Dear Sir:

I have your letter of March 6th enclosing letter from Gene Rhodes, with a clipping concerning the Lee case.

I am exceedingly desirous of assisting Gene in any way possible consistent of duty to friends and clients.

I note that he appreciates the possible objections to advertising the Lee Case at this time. Mr. Lee is a prominent citizen of Otero County, New Mexico, and a man of property. Unfortunately, he and his friends were placed in a position where they were at one time considered out-laws.

The Lee case was dragged into politics and the legislature controlled by those opposed to the party to which Lee belonged, offered rewards for evidence, etc. and also for the purpose of securing additional counsel for the prosecution of Lee and his companions. The newspapers in New Mexico were full of the case, and upon final trial at the little country town of Hillsboro, 15 or 16 miles from the end of the railroad, representatives not only of the newspapers in the Southwest, but the Manager for the Associated Press at Denver were present during the trial, and a special telegraph line was built from the railroad to Hillsboro for the occasion, and an operator employed for the term of court. The Los Angeles Times and other papers in the Southwest, published from day to day the evidence offered.

Col. A.J. Fountain was or had been a Mason, and it was claimed that the Masonic Order in New Mexico raised funds with which to assist in the prosecution of Lee.

I am reciting these facts simply that you may be able to understand my reasons for not approving any actions which might rake up the old story. There are so many people living in New Mexico and elsewhere, who were dragged into this case, that I think nothing further should be said about it at the present time.

To serve the interest of Gene Rhodes in any way, facts would have to be given and proper names used, and old animosities rearoused, particularly in New Mexico.

Gene Rhodes is a unique character and I am personally very fond of him. I have more than once urged that he should return to New Mexico for two or three months’ visit with his old friends there.

If I can assist in any way in advancing Rhodes’ interests, I will be glad to do so, but in this particular matter of the old Lee case, I do not think that either his interest or those of the public would be served by calling attention to it, while discussion of the case might renew old “sore spots” and cause trouble.

Conditions in the Southwest, while of course, are not as existed twenty or even fifteen years ago, are not as those as exist in New York. Even yet people carry six-shooters in New Mexico, and upon occasion use them. The open range exists in no other part of the United States as in New Mexico and Arizona. There can yet be found a cow puncher in something of his pristine glory.

This Lee case involved hundreds of people arrayed upon one side or the other, not only in a political but personal feud. Many of these people, in fact the majority are yet alive. The old animosities have been buried and we must let them lie.

Very sincerely yours,

[A. B. Fall]”

Albert Fall’s letter to Roland Holt is a revelation. It helps explain, for example, why the fight at Wildy Well or the entire story of the Fountain murders has drawn relatively little literary attention in comparison to Pat Garrett’s confrontation with Billy the Kid or the shootout at the OK Corral between the Earps, Doc Holiday, and the Clantons, both of which were widely publicized a few years after their occurrence. It also helps explain why the bright light of a major advertising campaign was not used to illuminate Eugene Manlove Rhodes as a player in one of the most dramatic true stories to come out of the southwest. It was the kind of story that showed Rhodes to be a true man of the real west, the kind for which the public hungered, and its telling across the country might have projected him and his tales forward into the modern imagination.

Albert Fall was correct. The story of Oliver Lee, Jim Gililland, Eugene Rhodes, and Pat Garrett needed to rest a long time gathering the dust and perspective of years before it was resurrected. New Mexico men in the Tularosa basin still carried guns in 1915 and weren’t reluctant to use them for settling old grievances. It was best, then, to let old wounds continue to heal.

Today, it is time to give Eugene Manlove Rhodes, too long overlooked, the widespread recognition he has long deserved for his superb western writing, writing that was based on real life experience.

![]()

Sources: Keleher, William A., The Fabulous Frontier, The Rydal Press, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 1945.; Hutchinson, W. H., A Bar Cross Man, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma, 1956.; Recko, Corey, Murder on the White Sands, University of North Texas Press, Denton, Texas, 2007. ; Metz, Leon, Pat Garrett, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma, 1974. ; Sonnichsen, C. L., Tularosa Last of the Frontier West, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1960. Public domain images via Wikipedia.